Labels, Likeness, and the AI Conundrum

Do labels own an artist's voice? What will happen to recording agreements in response to the proliferation of AI?

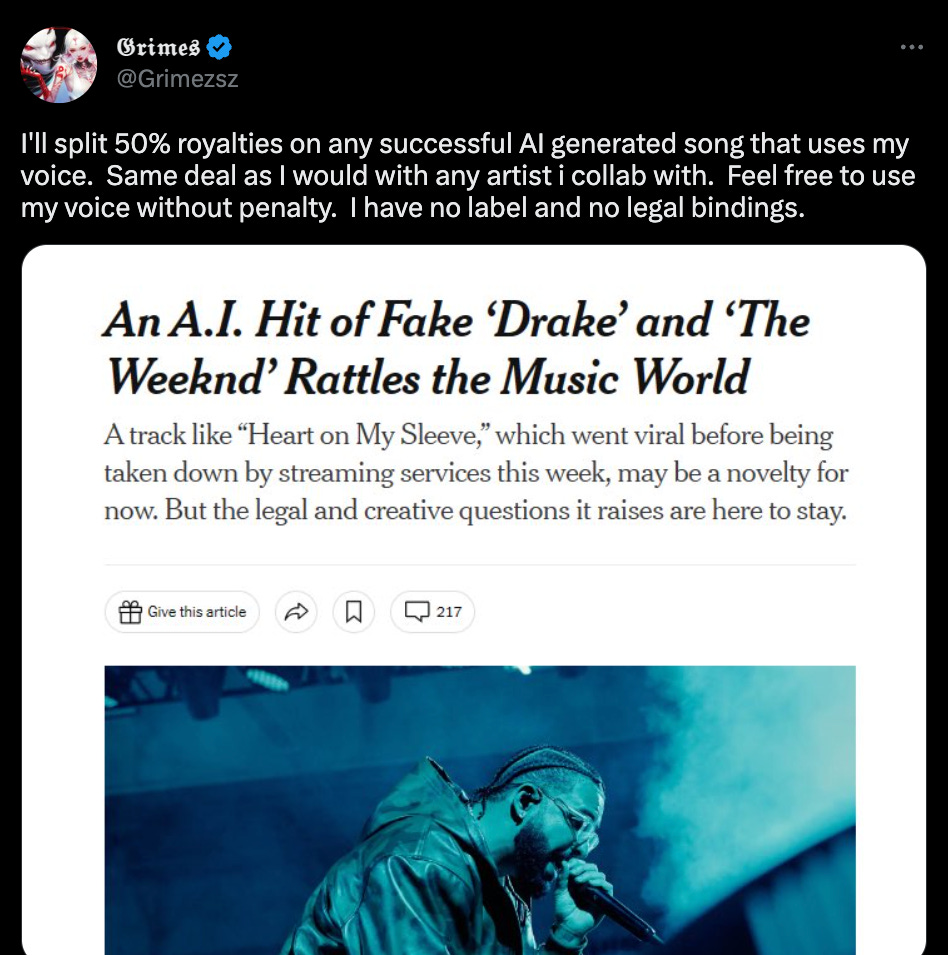

In the wake of the “Heart on My Sleeve” controversy, Grimes is encouraging the use of her voice via AI and relinquishing an equitable split to creators. This marks one of the first public embraces of the technology - and inevitable future - by a name brand artist.

Unencumbered by a label deal, Grimes has the flexibility for such experiments. Universal Music Group (UMG), to which both Drake and The Weeknd are signed, worked overtime to issue takedowns as “Heart on My Sleeve” spawned across streaming services. And this response was warranted given the lack of approval or license of either artist’s voice.

But could a recording agreement actually preclude an artist from following in Grimes’ footsteps? If a signed artist created and released an AI voice model from which new original works were created by other artists, would these new tracks fall under the recording agreement?

Let’s try and answer these questions using Kanye’s leaked recording agreements. Admittedly, these are dated; the original deal between Kanye and Roc-A-Fella (RAF) was struck in April 2005 and subsequently amended numerous times after RAF was acquired by Island Def Jam. The agreements aren’t perfect, but they’re publicly available and give us a baseline for how the voice and likeness of budding superstars might be treated by the legalese of an agreement.

Interestingly, voice is not addressed independent of likeness in the agreements. Thus, I’m inferring that likeness, which typically refers to visual representations of a person, also includes the artist’s voice in this context. Both voice and likeness are typically protected under the right of publicity which is the inherent right of every person to control the use of their identity. The right is: designed to protect people against unauthorized exploitation of their identity for commercial purposes, implemented via wide-ranging state legislation, and currently recognized in 35 states.

Recording agreements are struck between the label (RAF in this instance), the Artist (Kanye), and in this case a Grantor (Kanye’s production company Rock the World), or an entity that acts on behalf of the artist. The recording obligation specifies exclusivity during the term as well as a minimum output expected from the artist. The label is also entitled to anything beyond the minimum that’s recorded during the term.

The rights section is where things get interesting. The word ‘embody’ is encapsulating in that it covers an ‘expression or tangible, visible form’ of the artist. It can be argued that tracks created from a voice model would certainly be an expression both from and of the artist.

Derivative works, which have become increasingly prevalent in the TikTok era, are understandably covered in the agreement. Whether or not a track created using the voice model would constitute a derivative work might hinge upon whether the model was trained using master recordings owned by the label. If the model was provably trained by the artist’s voice from snippets of content recorded prior to the agreement term, then there might be a case for the content created using the model to sit outside the agreement.

After all, later in the section, the language explicitly states that the label merely has a perpetual license to use the artist’s likeness in connection with the promotion of records. But, importantly, the label doesn’t own the artist’s likeness during the term and ensures in the language that its use will not infringe upon the artist in any way.

Later in the Grantor’s Reps & Warranties section, the agreement prohibits the artist from licensing his likeness for any recording that ‘embodies’ (i.e., resembles) any composition covered by the agreement. The important distinction here is the resemblance to a master recording.

If the artist were to act or license his voice for use in a film or commercial, the label wouldn’t have recourse to participate provided the performance is ‘non-musical.’

Finally, there is a clause that broadly prohibits the artist from doing anything that would reduce the label’s rights or harm the record industry. It can be argued that a voice model would do both of these things if the label wasn’t cut in on it, and the broad language leaves a wide margin for interpretation.

What Next?

So where does this leave us? One big gray area.

With the proliferation of AI, it stands to reason that UMG and other labels will scramble to amend recording agreements with language that explicitly addresses the technology. There is recent precedent for this type of protective response. As Taylor Swift’s re-rerecorded tracks began to outperform their original counterparts, UMG swiftly doubled the re-record restriction period in its agreements.

But while contract amendments are a natural and defensive response, it might behoove UMG and other labels to go on the offensive as well. Build or license the technology to create voice models for roster artists on an opt-in basis. Create a compliant avenue for this type of content, amplify an artist’s brand, and unlock a new revenue stream in the process. Provide the infrastructure for opted-in artists to execute on the opportunity, or fight potential circumvention of recording agreements. Rob Abelow gives us the blueprint on how to execute in last week’s Where Music is Going. Doing so is no easy technological lift. Grimes has her own neural network and tech platform - Elf Tech - providing voice access and managing registration, royalties, and enforcement. Labels become an even more enticing partner for an artist when they can offer this.

And what could be a more powerful proposition for fans than seamless co-creation (in a sense) with their favorite artists? Sure, some artists and rights holders will recoil at this notion. Lack of scarcity. Art devaluation. But others will embrace it. The ‘street team of marketers’ that was promised by royalty investing platforms can be actualized through AI-based co-creation.

Providing this infrastructure, however, would be in complete opposition to the public condemnation UMG has leveled at generative AI thus far. Yes, there has been rampant copyright infringement, and we do run the risk of exacerbating the content oversupply issue as I touched on in a prior piece. But I think Peter Gabriel hit the nail on the head with his statement:

When the future has shown itself so clearly and is flowing as fast as a river after a storm, it seems wiser to swim with the current. AI is here. Let’s learn what we can and how we might adapt and evolve it to better serve everyone.

Brace yourself for the new world.

Sources (of inspiration)

AI Competition Statement - Peter Gabriel

Is Deep Fake Drake Just a Remix - Jessica Powell

As Taylor Swift Re-Recorded Her Red Album, UMG Reworked Contracts - Wall Street Journal

Why is Spotify full of faster versions of pop hits? - The Guardian

UMG makes it more difficult for artists to re-record their work - The Verge

UMG Targets Name & Likeness Acquisitions in Deal with ABG - MBW

UMG Issues its Sternest Warning Yet on AI - Digital Music News

A Recording Artist’s Right to Publicity - IP Law Journal (University of Georgia)

Right to Publicity - American Bar Association

Legal Disclaimer

The above is in no way intended to be legal advice and should not be construed as such. All information, content, and third-party links are for general informational purposes only. Information in this piece may not constitute the most up-to-date legal or other information.